output – interview

With Patricia de Vries, Liza Prins and Maisa Imamović

The research group Art & Spatial Praxis launched the digital artistic research platform Plot(ting) on April 17th. Plot(ting) emerges as a publishing platform showcasing art, research, and spatial practices.

Inspired by the theories of Jamaican critic Sylvia Wynter on space and narrative, Plot(ting) investigates ‘plotting’ as a form of artistic practice. The publication features a diverse array of contributions that extend beyond the written word, including dance and lecture-performances, audio landscapes, video art, and photography. These works collectively offer innovative perspectives on spatial relationships and artistic intervention.

In this interview with Patricia de Vries, lector of the Art & Spatial Praxis research group, projectcoordinator Liza Prins and webdesigner & developer Maisa Imamović you read more about the platform and it’s development.

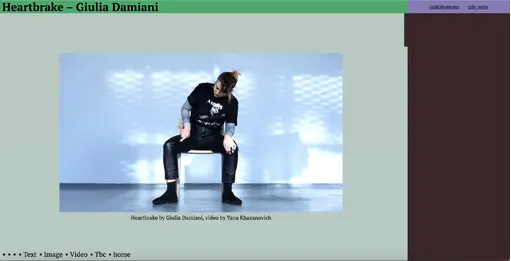

'Plot(ting)' currently harbors contributions by Flavia Pinheiro, Giulia Damiani, Francisca Khamis & Maia Gattás Vargas, Neeltje ten Westenend & Hanneke Stuit, Mariana Balvanera, Patricia de Vries, Amelia Groom, and Liza Prins.

plotting.rietveldsandberg.nl

This platform is developed in partnership with Institute of Network Cultures (INC) and generously supported by Centre of Expertise for Creative Innovation (CoECI).

In this interview with Patricia de Vries, lector of the Art & Spatial Praxis research group, projectcoordinator Liza Prins and webdesigner & developer Maisa Imamović you read more about the platform and it’s development.

'Plot(ting)' currently harbors contributions by Flavia Pinheiro, Giulia Damiani, Francisca Khamis & Maia Gattás Vargas, Neeltje ten Westenend & Hanneke Stuit, Mariana Balvanera, Patricia de Vries, Amelia Groom, and Liza Prins.

plotting.rietveldsandberg.nl

This platform is developed in partnership with Institute of Network Cultures (INC) and generously supported by Centre of Expertise for Creative Innovation (CoECI).

The research group Art & Spatial Praxis launched the digital artistic research platform Plot(ting) on April 17th 2024. Plot(ting) emerges as a publishing platform showcasing art, research, and spatial practices. Currently it harbors contributions by Flavia Pinheiro, Giulia Damiani, Francisca Khamis & Maia Gattás Vargas, Neeltje ten Westenend & Hanneke Stuit, Mariana Balvanera, Patricia de Vries, Amelia Groom, and Liza Prins. Here you can read in brief about the different contributions. Read more on the plotting website: plotting.rietveldsandberg.nl

Video of the launch of the publication of Plot(ting) on April 17th 2024, hosted at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie. Performances and talks by: meLê yamomo, S*an D. Henry Smith, Francisca Khamis Giacoman, Derica Shields, Patricia de Vries, Liza Prins and Maisa Imamović.

Patricia, you are the initiator of the digital artistic research platform Plot(ting). Could you elaborate on why you wanted to set up this platform?

PdV: The research group Art & Spatial Praxis explores how artists, academics, and activists can challenge capitalist structures, such as cities, urban developments, institutes, and infrastructures. How do they create spaces, even if temporarily, within these systems while avoiding being co-opted by them? How do they reinterpret and reclaim spaces, spatial relationships, and practices? These questions are relevant to a wide range of disciplines and often they involve practices that cannot be fully expressed through text alone.

The plotting platform is the result of a collaboration between Art & Spatial Praxis and the Institute of Network Cultures. The Institute of Network Cultures explores the possibilities of Expanded Publishing (EP), which is a cross-media approach to publishing. It experiments with practice-based research that cannot be captured in text alone. The goal is to find ways to publish, share, and communicate forms of research and art practices that go beyond plain text and images. The platform aims to explore publishing practices that go beyond just using the written word. As you’ll see, the platform features contributions that extend beyond writing, including dance and lecture-performances, audio landscapes, letters, video, and photography.

The plotting platform is the result of a collaboration between Art & Spatial Praxis and the Institute of Network Cultures. The Institute of Network Cultures explores the possibilities of Expanded Publishing (EP), which is a cross-media approach to publishing. It experiments with practice-based research that cannot be captured in text alone. The goal is to find ways to publish, share, and communicate forms of research and art practices that go beyond plain text and images. The platform aims to explore publishing practices that go beyond just using the written word. As you’ll see, the platform features contributions that extend beyond writing, including dance and lecture-performances, audio landscapes, letters, video, and photography.

Why is the platform called Plot(ting)?

PdV: I am inspired by Jamaican theorist Sylvia Wynter and her ground-breaking theories on Marxism, space, and narrative. I examine Wynter’s concept of the plot as a form of art and spatial praxis. Sylvia Wynter draws striking connections between the historical plantation system and contemporary societal structures, linking the plantation system to issues such as climate change, poverty, surveillance, policing, segregation, gentrification, and the suppression of people of colour. She argues that these seemingly disparate phenomena are deeply intertwined with the enduring legacy of the colonial plantation model, persisting in today's global racial capitalist production systems that exploit nature, labour, bodies, time, lives, ecologies, and animals for profit.

However, Wynter also points to the concept of the plot as distinct yet intertwined with the plantation. Plots were provision grounds enslaved Africans could cultivate. On these grounds, often at some distance from the villages of the plantation, the enslaved could grow their own food. Plantation owners made these plots of land available to reduce costs. These plots were places where enslaved people collaborated in relation to, but also in relative autonomy from, the violence of the plantation. In Wynter’s work, the plot represents regenerative agriculture, indigenous knowledge, and resistance that existed alongside the extractive logic and violence of the plantation. Yet plots were also products of the plantation; the relation between the plot and the plantation is ambivalent, a source of alienation and potential resistance.

Wynter’s discussion of the plot concept is also ambivalent. It is a historical reality and a metaphor. In her work “plot” is a noun referring to a physical space and a verb for counter-hegemonic and decolonial narratives and practices. It also refers to what she calls “underlife” culture. Wynter draws lines of connection between the plots, the cultivation of yam, jazz and ska music, and the hippies movement, climate justice and women’s movement.

The plot is then a concept, a metaphor, a historical reality, and a verb. It is a conceptual tool and historical reality. It is figurative language and a challenge to current spatial arrangements. It is a verb and a narrative device. The plot signifies practices in which other values are acted upon, constituted, grounded, and where dominant social orders and values are challenged and evaded. ‘Plot(ting)’ is an attempt to capture some of these layered meanings.

Wynter’s plot concept is recognised in decolonial studies, critical race studies, comparative literature, geography, and philosophy. I think the plot concept has great potential for further exploration in the arts, activism, and academia. Plot(ting) investigates the plot as a model for such practices, examining how artists, writers, and scholars can challenge capitalist enclosures, both past and present.

However, Wynter also points to the concept of the plot as distinct yet intertwined with the plantation. Plots were provision grounds enslaved Africans could cultivate. On these grounds, often at some distance from the villages of the plantation, the enslaved could grow their own food. Plantation owners made these plots of land available to reduce costs. These plots were places where enslaved people collaborated in relation to, but also in relative autonomy from, the violence of the plantation. In Wynter’s work, the plot represents regenerative agriculture, indigenous knowledge, and resistance that existed alongside the extractive logic and violence of the plantation. Yet plots were also products of the plantation; the relation between the plot and the plantation is ambivalent, a source of alienation and potential resistance.

Wynter’s discussion of the plot concept is also ambivalent. It is a historical reality and a metaphor. In her work “plot” is a noun referring to a physical space and a verb for counter-hegemonic and decolonial narratives and practices. It also refers to what she calls “underlife” culture. Wynter draws lines of connection between the plots, the cultivation of yam, jazz and ska music, and the hippies movement, climate justice and women’s movement.

The plot is then a concept, a metaphor, a historical reality, and a verb. It is a conceptual tool and historical reality. It is figurative language and a challenge to current spatial arrangements. It is a verb and a narrative device. The plot signifies practices in which other values are acted upon, constituted, grounded, and where dominant social orders and values are challenged and evaded. ‘Plot(ting)’ is an attempt to capture some of these layered meanings.

Wynter’s plot concept is recognised in decolonial studies, critical race studies, comparative literature, geography, and philosophy. I think the plot concept has great potential for further exploration in the arts, activism, and academia. Plot(ting) investigates the plot as a model for such practices, examining how artists, writers, and scholars can challenge capitalist enclosures, both past and present.

What can we find on the platform?

PdV: Plot(ting) investigates how artists, academics and activists can challenge institutional and capitalist norms to foster different forms of understanding, being, and social relation. In the contributions to Plot(ting), different aspects of the concept of the plot are staged, embodied, narrated, explored, and materialised. The publication shows possibilities of what “plot” and “plotting” might be in contemporary research and artistic practice. It includes dance performances, soundscapes, video art, lecture performance, photography, and also text. Contributions to Plot(ting) cover various subjects and objects, from Dutch domestic colonies and the materiality of mud to personal letter exchanges.

Liza, you coordinated the development of this platform. What thoughts and considerations did you give Maisa to work with?

LP: This project developed as a continuous dialogue between Maisa and me, and I am very grateful for her generosity in sharing her knowledge and insights from a feminist, nonconformist practice of web development. Creating a platform that could display many forms of study, both creative and more conventionally academic, in a non-hierarchical manner was the original "prompt." The website's open-ended design was another crucial component; rather than just showcasing projects, it is a growing archive nurturing a discursive space - with Plot(ting) and Sylvia Wynter's scholarship as its anchor. A final consideration was the experience of a visitor to the website. It was important to us that the platform's content and infrastructure would challenge readers and that an exploratory experience was prioritized over conventional, or even dogmatic, tools for "user-friendliness." I think Maisa did a phenomenal job embedding our wishes and fantasies for the website and I am so happy we got to collaborate on it.

Maisa, can you tell us how you decided to show the contributions and in what ways this diverges from more traditional strategies for websites as publication formats and archiving platforms?

MI: At the beginning of our collaboration, I was told that the website had to be non-linear. In web design, non-linearity is often designed in a way that it hides the grid because the grid makes the website look square-y. By hiding it, the content items look like they’re floating — an effect that refers to their freedom. In another case of non-linear web design, a website has integrated a horizontal scroll to play with the expectations of the user, as well as expand their sense of the web page’s size. Yet in other cases, non-linearity is an imagery suggestion, animated, frameless, etc…In all these cases, non-linearity depends on the grid and cannot exist without it. In web development and design, it’s very hard to avoid thinking through the grid and even harder to get rid of it. Because most websites are primarily concerned with user-friendliness which favors the grid (from traditional printed matter syntax), these design moves can’t go too far into breaking the linearity and rather become mere aesthetic gestures that tickle the user’s imagination that they cannot fulfill.

Traditional graphic designers who build websites often approach this issue by embracing the grid, exposing it, and perfecting it. That’s why they get bored of designing their own websites and oftentimes move towards back-end development where they can implement more of the same control they gained with their grid-centric designs. It often happens that they merge their grids with the architectural references of the spaces/institutions they’re working with, such as floor plans, office tables, images of the space, or any spatial element that refers to a fixed location where maintenance occurs. Their website is a mere digital translation of such power.

Because I don’t have a background in graphic design, I am slow at making visual connections to start designing from. I think about movement a lot, which is why I start building a website by first sketching the user experience. I love thinking about the user’s encounter with the website, their internet boredom, whether they’re indulging in digital trash or doing some sort of research, etc…Design follows from weaving these experiences.

This also means that I have to talk a lot with my collaborators. For this website, that person was Liza <3. During our design revision, I asked her if any colors or graphics naturally emerged during other events around Plot(ting) and she shared the image of a blanket with me. When I saw it, the ‘final’ design instantly appeared in my head. The image of the blanket’s pattern couldn’t have referred more to a grid than it did, but the mere fact that it was a blanket excited me very much – it also referred to movement and unfixed location. The blanket had to be a part of the website.

Traditional graphic designers who build websites often approach this issue by embracing the grid, exposing it, and perfecting it. That’s why they get bored of designing their own websites and oftentimes move towards back-end development where they can implement more of the same control they gained with their grid-centric designs. It often happens that they merge their grids with the architectural references of the spaces/institutions they’re working with, such as floor plans, office tables, images of the space, or any spatial element that refers to a fixed location where maintenance occurs. Their website is a mere digital translation of such power.

Because I don’t have a background in graphic design, I am slow at making visual connections to start designing from. I think about movement a lot, which is why I start building a website by first sketching the user experience. I love thinking about the user’s encounter with the website, their internet boredom, whether they’re indulging in digital trash or doing some sort of research, etc…Design follows from weaving these experiences.

This also means that I have to talk a lot with my collaborators. For this website, that person was Liza <3. During our design revision, I asked her if any colors or graphics naturally emerged during other events around Plot(ting) and she shared the image of a blanket with me. When I saw it, the ‘final’ design instantly appeared in my head. The image of the blanket’s pattern couldn’t have referred more to a grid than it did, but the mere fact that it was a blanket excited me very much – it also referred to movement and unfixed location. The blanket had to be a part of the website.

Maisa, you worked with the tension between prioritizing user-friendliness and challenging conventional expectations in website development. Could you elaborate on instances within the platform where the explorative movements of the user are emphasized?

MI: At first, I literally translated the blanket’s design into the website’s design. It was just a grid with four squares of the same size and different colors. It was fixed and challenging to break. I then started thinking that If I placed the text on top of this grid, it’d be readable only where the square is light green. If I placed the text on top of darker squares, I’d have to change the text color to a brighter one, which would then not be readable in the light green square. I found this challenge exciting to work with because I could start imagining the movement’s choreography. I decided that the grid/blanket would have to change ‘moods’ by changing the size of each square on the grid. There are different moods across the homepage, category pages, and article pages. These decisions were focused on making the initially user-unfriendly grid friendly. I think it worked.

To add more exploration to the user experience, I decided to shuffle the order and positions of the article titles, wherever they appear in a group. They’re to be found on the homepage, category pages, and at the bottom of each article.

To add more exploration to the user experience, I decided to shuffle the order and positions of the article titles, wherever they appear in a group. They’re to be found on the homepage, category pages, and at the bottom of each article.

What is your favourite part of the website?

MI: Each article page has a sidebar to the right that shows either a footnotes list or a text area that enables users to take personal notes which they can then download locally on their machines as a .txt file. I love that corner of the page! Within a moving environment, it suggests that the user slows down and builds a personal reading pace of the theory-heavy articles.

LP: I'm afraid I can't choose between two of my favorite features. First and foremost, I appreciate how the color blocks - purple, beige, green, and brown - (re)create a material condition for the Plot(ting) meetings as we have been organizing them; online, these meetings take place when the various contributions are placed and re-arranged on this backdrop; offline, our research group has been meeting in different locations on a blanket in these same colors - a material marker for our temporary (re)claimed spaces.

The second feature I particularly love is the note-taking capability. I think it's a great little reminder that as a reader, you're also active while reading, watching, and listening to work on the platform; a slight push to improve an, or your, agential learning habit. I am still amazed by how Maisa developed these moments or tools that, in my opinion, actualize what plot(ting) could be.

PdV: The footnotes are on the side. That is my favourite intervention. Brilliant work of Maisa. Bow down. I’ve seen it once or twice in some art book, but rarely, if ever, online.

LP: I'm afraid I can't choose between two of my favorite features. First and foremost, I appreciate how the color blocks - purple, beige, green, and brown - (re)create a material condition for the Plot(ting) meetings as we have been organizing them; online, these meetings take place when the various contributions are placed and re-arranged on this backdrop; offline, our research group has been meeting in different locations on a blanket in these same colors - a material marker for our temporary (re)claimed spaces.

The second feature I particularly love is the note-taking capability. I think it's a great little reminder that as a reader, you're also active while reading, watching, and listening to work on the platform; a slight push to improve an, or your, agential learning habit. I am still amazed by how Maisa developed these moments or tools that, in my opinion, actualize what plot(ting) could be.

PdV: The footnotes are on the side. That is my favourite intervention. Brilliant work of Maisa. Bow down. I’ve seen it once or twice in some art book, but rarely, if ever, online.

Patricia, what are your plans for the future of the platform? How will the platform continue to grow? Can artistic researchers reach out when they want their research published on the Plot(ting) platform?

PdV: This platform is meant to grow into a repository of practices that resonate with its core theme – plot(ting) – serving as a growing archive and a publishing platform. Its aim is to collect and bring together initiatives that testify to the power of decolonial and counter-hegemonic practices & narratives. Plot(ting) aims to become an open archive and a platform for publication. It seeks to provide a space for creators and scholars whose work aligns with Sylvia Wynter’s concept of ‘the plot.’ Alongside my co-editor, Amelia Groom, we will collaborate with five contributors in the near future. By early 2025, we plan to issue an open call for contributions.

lector/professor

Patricia de Vries is a research professor of Art & Spatial Praxis at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie. Art & Spatial Praxis is a research group focusing on art, activist, and academic practices that intervene in capitalist enclosures such as cities, urban developments, institutes, and infrastructures. Her ongoing research project, Plot(ting), is an expanding open archive and a research platform for publication.

Liza Prins is an artist, researcher, and writer based in Amsterdam. Her work focuses on feminized and pre-industrial labor, as well as the material and immaterial conditions and tools for social organization that emerge from it. Using collaborative performative methods touching on re-enactment techniques and improvisation, she seeks to re-establish a connection with material histories and social imaginations.

Maisa Imamović is a web designer/developer and a researcher interested in building hybrid publishing formats and collectively built interfaces. In her research, she critically studies the role of a single user and user behaviors generated by code.